What is Shiva Called in Buddhism?

In Hinduism, Shiva is one of the principal deities, revered as a paramount figure within the religion’s extensive pantheon. Known as the “Destroyer” among the Trimurti, or Hindu trinity, which includes Brahma the Creator and Vishnu the Preserver, Shiva’s role is both complex and multi-faceted. He is not merely a harbinger of destruction but a transformer, embodying the cyclical nature of existence, where destruction paves the way for regeneration and renewal.

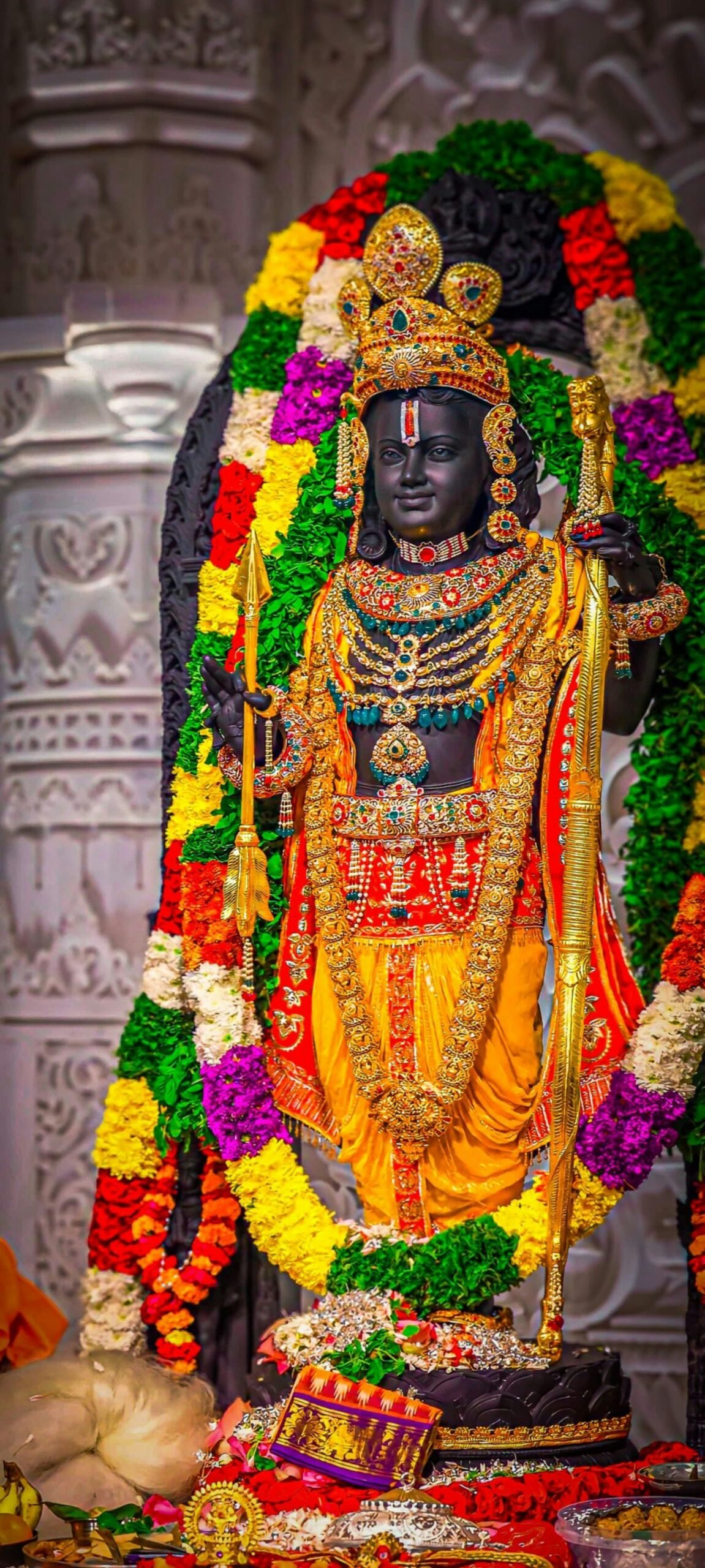

Shiva is often depicted in deep meditation, symbolizing his role as a yogi, and is associated with attributes such as the third eye, which signifies wisdom and insight; the crescent moon, representing the cycle of time; and the trident, denoting his dominion over the three aspects of life: creation, preservation, and destruction. His blue throat, the result of consuming poison to save the universe, underscores his role as the protector and savior.

Integral to Hindu practices, Shiva’s influence permeates various aspects of spiritual and daily life. Devotees worship him in numerous forms and manifestations, such as the iconic Shiva Linga, a symbol of his formless aspect, and through rituals like the Maha Shivaratri festival, which celebrates his divine dance, the Tandava, believed to be the source of cosmic rhythm. Myths and legends surrounding Shiva are abundant, illustrating his complex nature and his interactions with other deities, demons, and human beings.

Shiva’s significance extends beyond religious practices to cultural and philosophical domains, embodying the principles of destruction and rebirth that are essential to understanding the Hindu worldview. His presence in temples, literature, and art across India and beyond speaks to his enduring impact and the profound reverence he commands among his followers.

Buddhist Adaptation of Hindu Deities

Buddhism, having originated in India where Hinduism was already deeply rooted, naturally engaged in a complex and nuanced dialogue with the pre-existing religious landscape. This interaction led to the adaptation and transformation of certain Hindu deities within Buddhist traditions. The phenomenon of syncretism, where elements of different religious traditions are blended, and cultural exchange played pivotal roles in this adaptation process.

In ancient India, the boundaries between Hinduism and Buddhism were often fluid, allowing for a rich exchange of ideas and practices. Deities from Hinduism were incorporated into Buddhist cosmology, often taking on new roles and interpretations. A prime example is the Hindu god Shiva, who, despite being a central figure in Hinduism, found a place in Buddhist traditions as well. In Buddhism, Shiva is often reinterpreted as a guardian deity or a protective figure, illustrating the syncretic nature of these religious traditions.

This cultural and religious interplay was not one-sided. Buddhist figures and concepts influenced Hindu practices and iconography, creating a dynamic exchange that enriched both traditions. For instance, the Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara, known for his compassion, has parallels with the Hindu deity Vishnu, particularly in his role as a preserver and protector.

The adaptation of Hindu deities into Buddhism was not merely a superficial borrowing but involved significant reinterpretation to fit the philosophical and doctrinal frameworks of Buddhism. This process allowed Buddhism to resonate with the local populace who were familiar with Hindu deities, facilitating its spread and acceptance. Moreover, it reflects the broader cultural and religious milieu of ancient India, characterized by a high degree of pluralism and mutual influence.

Thus, the adaptation of Hindu deities into Buddhist traditions exemplifies the intricate tapestry of religious and cultural exchange in ancient India. It underscores the fluidity and interconnectedness of religious identities and highlights the role of syncretism in shaping the religious landscape of the region. This blending and reinterpretation enriched both Hindu and Buddhist traditions, leaving a lasting legacy on the spiritual heritage of the region.

Shiva in Buddhist Texts and Iconography

Shiva’s presence in Buddhist texts and iconography is a fascinating aspect that underscores the syncretic nature of religious traditions in South Asia. In Buddhist scriptures, Shiva is often referenced in the context of Mahayana and Vajrayana traditions. For example, in the Mahayana text “Sutra of Golden Light,” Shiva is mentioned as a deity who pays homage to the Buddha. This indicates a level of reverence and acknowledgment of Shiva within Buddhist teachings, although his role is not as central as in Hinduism.

In Vajrayana Buddhism, particularly in the Tibetan tradition, Shiva is often depicted in the form of Mahakala. Mahakala is considered a protector deity and is revered for his fierce and powerful attributes, which are somewhat analogous to Shiva’s role as a destroyer and regenerator in Hinduism. This transformation of Shiva into Mahakala highlights the adaptability and integration of Hindu deities into Buddhist practices.

When it comes to iconography, Shiva’s depiction in Buddhist art varies but usually maintains certain core attributes recognizable from Hindu portrayals. In some Buddhist sculptures and paintings, Shiva is shown with his traditional attributes such as the trident (trishula), the crescent moon, and the third eye on his forehead. However, these depictions often incorporate Buddhist symbols and motifs, blending the two religious iconographies harmoniously.

The similarities in Shiva’s portrayal in both Hinduism and Buddhism include his appearance as a deity associated with destruction and transformation, as well as his role as a protector. The differences, however, are significant in terms of the context and emphasis placed on his attributes. While Hinduism places Shiva at the core of its trinity (Trimurti), Buddhism integrates Shiva within its broader pantheon of deities, often reinterpreting his characteristics to align with Buddhist principles of compassion and enlightenment.

Overall, the portrayal of Shiva in Buddhist texts and iconography reflects a unique blend of reverence and adaptation, demonstrating the fluid and interconnected nature of South Asian religious traditions.

The Role of Mahākāla in Vajrayana Buddhism

Mahākāla is a prominent deity in Vajrayana Buddhism, often regarded as an equivalent or an aspect of Shiva, the Hindu god of destruction and transformation. In the context of Tibetan Buddhism, Mahākāla is revered as a fierce protector of the Dharma, embodying the qualities of both wrath and compassion. His primary role is to safeguard spiritual practitioners against obstacles and negative forces, ensuring the preservation and propagation of Buddhist teachings.

Mahākāla’s depiction is typically menacing, featuring a dark complexion, multiple arms, and a crown of skulls, symbolizing his power over death and his ability to annihilate delusions. These attributes closely align with those of Shiva, who is also known for his destructive capabilities, often represented through his dance of destruction, the Tandava. Both deities share the common purpose of removing ignorance and paving the way for spiritual enlightenment.

In Tibetan Buddhist practices, Mahākāla’s significance is profound. He is frequently invoked during rituals and meditations aimed at overcoming inner and outer obstacles. Monasteries and temples often dedicate shrines to Mahākāla, where monks and practitioners recite prayers, perform rituals, and make offerings to seek his protection and blessings. His fierce demeanor is not seen as malevolent but rather as a powerful force that combats negativity and supports spiritual growth.

Comparing Mahākāla’s attributes with those of Shiva reveals several similarities. Both deities are associated with the destruction of ignorance and the transformation of the self. Shiva’s role as the destroyer in the Hindu trinity (Trimurti) parallels Mahākāla’s function as a Dharma protector. Additionally, both are often depicted in formidable forms, emphasizing their capability to overcome evil and ignorance. Despite their fearsome appearances, the underlying essence of both deities is deeply compassionate, aimed at facilitating the spiritual evolution of their devotees.

Shiva as Lokeshvara (Avalokiteshvara) in Mahayana Buddhism

In the realm of Mahayana Buddhism, a fascinating identification emerges between Shiva and Avalokiteshvara, also known as Lokeshvara. Avalokiteshvara is revered as the bodhisattva of compassion, embodying the Buddhist ideal of boundless mercy towards all sentient beings. This compassion-centric figure shares intriguing parallels with certain aspects of Shiva, particularly his role as a guardian and benefactor.

Avalokiteshvara, whose name means “The Lord Who Looks Down with Compassion,” is depicted in numerous Mahayana texts as a savior who listens to the cries of beings in distress and offers them relief. The Karandavyuha Sutra, a prominent Mahayana scripture, extols Avalokiteshvara’s infinite compassion and his commitment to aiding those who invoke his name. This emphasis on compassion aligns closely with Shiva’s benevolent aspects, especially as manifested in his roles as a protector and a healer in Hindu traditions.

Some Mahayana traditions draw direct correlations between Shiva and Avalokiteshvara, suggesting that both deities fulfill similar functions within their respective spiritual frameworks. For instance, Shiva’s epithet “Mahadeva,” meaning the Great God, is mirrored by Avalokiteshvara’s designation as the supreme compassionate being. Furthermore, the iconography of Avalokiteshvara, often depicted with multiple arms and serene expressions, can be seen as an echo of Shiva’s multi-faceted and compassionate nature.

Textual evidence from various Mahayana sources supports this identification. In the “Saddharma Pundarika Sutra” (Lotus Sutra), Avalokiteshvara’s ability to manifest in different forms to help beings resonate with Shiva’s capacity to assume various avatars for the welfare of the world. This adaptability and commitment to alleviating suffering highlight the shared compassionate ethos between the two deities.

Thus, while Shiva and Avalokiteshvara originate from distinct religious traditions, their shared characteristics as compassionate protectors create a significant point of convergence. This identification underscores the universal value of compassion across spiritual boundaries, enriching both Hindu and Buddhist traditions.

Shiva and the Concept of Adi-Buddha

In certain Buddhist traditions, the concept of the Adi-Buddha, or the primordial Buddha, plays a significant role in understanding the origins and nature of divine figures. The Adi-Buddha is often seen as the first or original Buddha from whom all other Buddhas emanate. Interestingly, there are instances where Shiva, a prominent deity in Hinduism, is associated with the Adi-Buddha. This association primarily emerges in Tantric Buddhism, particularly within some schools of Vajrayana Buddhism.

The identification of Shiva with the Adi-Buddha can be traced back to syncretic influences where Hindu and Buddhist practices overlapped. Philosophically, this association suggests a convergence of divine archetypes across religious traditions. Shiva, known for his roles as the creator, preserver, and destroyer in Hinduism, embodies qualities that resonate with the concept of the Adi-Buddha, who is seen as the source of all creation and enlightenment in Buddhism.

Several key texts and teachings support this association. For instance, the “Hevajra Tantra,” a seminal text in Tantric Buddhism, mentions Shiva within its teachings, highlighting the fluid boundaries between Hindu and Buddhist metaphysical thought. Additionally, the “Mahayoga” and “Yogini” tantras often incorporate Shiva-like figures, emphasizing his transformative powers akin to those attributed to the Adi-Buddha.

The philosophical implications of this identification are profound. It suggests a shared understanding of divine attributes across Hinduism and Buddhism, offering a broader, more inclusive perspective of divinity. This convergence also impacts the way divine figures are venerated and understood in these traditions, promoting a more integrated approach to spiritual practice and enlightenment.

By acknowledging the association between Shiva and the Adi-Buddha, scholars and practitioners can appreciate the rich tapestry of religious and philosophical thought that bridges diverse traditions. This understanding not only enhances the study of Buddhism but also fosters a deeper appreciation for the interconnectedness of spiritual concepts across cultures.

Cultural and Regional Variations

The interpretation and worship of Shiva within Buddhist traditions across Asia exhibit notable regional variations, influenced significantly by local cultures and traditions. In Tibetan Buddhism, Shiva is often identified with the deity Mahākāla, a fierce protector and dharmapala. Mahākāla plays a crucial role in Vajrayana practices, embodying the destructive and transformative power essential for overcoming obstacles on the path to enlightenment. Tibetan depictions of Shiva as Mahākāla typically emphasize his wrathful form, symbolizing both protection and the annihilation of negative forces.

In Nepalese Buddhism, Shiva is frequently integrated into the pantheon of deities worshipped by both Buddhists and Hindus. This syncretism is evident in the worship of Avalokiteshvara, where Shiva’s attributes are often merged with those of the compassionate bodhisattva. The blending of Hindu and Buddhist iconography in Nepal results in a unique depiction of Shiva that both honors his traditional attributes and aligns them with Buddhist principles of compassion and wisdom. This regional fusion underscores the harmonious coexistence of Hinduism and Buddhism in Nepalese culture.

Southeast Asian Buddhism, particularly in countries like Thailand and Cambodia, also showcases a distinctive interpretation of Shiva. Here, the influence of ancient Indian culture is evident in temple architecture and art. Shiva is often represented alongside Buddhist deities, reflecting the historical interactions between Hinduism and Buddhism in these regions. In Thailand, for example, the integration of Shiva within Buddhist contexts can be seen in the Phra Phrom shrines, where Shiva’s attributes are syncretized with local guardian spirits.

These regional variations highlight how local cultures and traditions profoundly shape the depiction and understanding of Shiva in Buddhist contexts. The adaptability and integration of Shiva into various Buddhist traditions across Asia demonstrate the fluidity of religious practices and the shared cultural heritage that transcends individual religious boundaries.

Conclusion: The Syncretic Legacy of Shiva in Buddhism

The intricate tapestry of religious traditions often reveals fascinating overlaps and exchanges, as illustrated by the presence of Shiva in Buddhist contexts. Throughout this exploration, we have observed how Shiva—primarily a deity within Hinduism—has been integrated into Buddhist practices and iconography, showcasing the syncretic nature of religious beliefs. This blending is not merely a historical curiosity but a testament to the fluidity and interconnectedness of religious identities.

The syncretic legacy of Shiva in Buddhism is evident in various forms, from the incorporation of Shiva-like figures in Buddhist art to the adaptation of specific attributes and symbolism in Buddhist texts. These examples underscore a mutual exchange where religious boundaries are permeable, allowing for a richer, more diverse spiritual landscape. This cultural and religious interplay highlights the human tendency to borrow and adapt elements from different traditions, leading to a more inclusive and comprehensive understanding of the divine.

Moreover, the enduring legacy of Shiva within Buddhism speaks to the broader implications for the study of religious and cultural exchanges. It encourages scholars and enthusiasts alike to look beyond rigid categorizations and appreciate the nuances of spiritual practices. By acknowledging the shared and borrowed aspects of religious traditions, we can foster a more holistic and empathetic view of global religions.

As we reflect on the syncretic legacy of Shiva in Buddhism, it becomes clear that religious identities are not static but are continually evolving through interaction and adaptation. This fluidity enhances our appreciation of the interconnectedness of all spiritual paths, reminding us that the quest for understanding the divine is a universal endeavor that transcends cultural and religious boundaries.

Leave a Reply